Dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates. Dorsal fins have evolved independently several times through convergent evolution adapting to marine environments, so the fins are not all homologous. They are found in most fish, in mammals such as whales, and in extinct ancient marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs. Most have only one dorsal fin, but some have two or three.

Wildlife biologists often use the distinctive nicks and wear patterns which develop on the dorsal fins of whales to identify individuals in the field.

The bones or cartilages that support the dorsal fin in fish are called pterygiophores.

Functions

[edit]The main purpose of the dorsal fin is usually to stabilize the animal against rolling and to assist in sudden turns. Some species have further adapted their dorsal fins to other uses. The sunfish uses the dorsal fin (and the anal fin) for propulsion. In anglerfish, the anterior of the dorsal fin is modified into a biological equivalent to a fishing pole and a lure known as an illicium or esca.

Some fishes have adapted their dorsal fins to defend against predators with sharp erect spines and venom, as in many species of catfish,[1] the spiny dogfish,[2] and perhaps the Port Jackson shark,[3]

- Dorsal fins evolved convergently; different species have 1, 2, or 3 of them.

-

Most fish, like this large goldfish, have one dorsal fin.

-

Sharks typically have two.

-

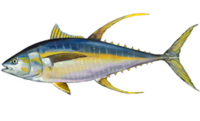

The yellowfin tuna has two.

-

Haddocks have three.

Billfish have prominent dorsal fins. Like tuna, mackerel and other scombroids, billfish streamline themselves by retracting their dorsal fins into a groove in their body when they swim.[4] The shape, size, position and colour of the dorsal fin varies with the type of billfish, and can be a simple way to identify a billfish species. For example, the white marlin has a dorsal fin with a curved front edge and is covered with black spots.[4] The huge dorsal fin, or sail, of the sailfish is kept retracted most of the time. Sailfish raise them if they want to herd a school of small fish, and after periods of high activity, presumably to cool down.[4][5] The great white shark's dorsal fin contains stabilizing dermal fibers that stiffen dynamically as it swims faster, helping it to control roll and yaw.[6]

- Some species have evolved specialist functions for their dorsal fins.

-

The African knifefish propels itself with its full-length dorsal fin, keeping its back straight for electrolocation.

-

Many catfish can lock their dorsal fin spines erect and secrete venom to discourage predators.

-

The great white shark's dorsal fin contains stabilizing dermal fibers that stiffen dynamically as it swims faster to control roll and yaw.

-

Large retractable dorsal fin of the Indo-Pacific sailfish may serve to control the fish's temperature.

- Dorsal fin shapes vary both within species and between related species.

-

Male and female orcas have differently shaped dorsal fins.

-

Ichthyosaurs had diverse dorsal fin shapes.

Structure

[edit]A dorsal fin is a medial, unpaired fin that is located on the midline of the backs of some aquatic vertebrates. In development of the embryo in teleost fish, the dorsal fin arises from sections of the skin that form a caudal fin fold.[7] The larval development and formation of the skeleton that support the median fins in adults result in pterygiophores. The skeletal elements of the pterygiophore includes basals and radials. The basals are located at the base of the dorsal fin, and are closest to the body. The radials extend outward from the body to support the rest of the fin.[7] These elements serve as attachment sites for epaxial muscles.[8] The muscles contract and pull against the basals of the pterygiophores along one side of the body, which helps the fish move through water by providing greater stability.[8] In these types of fish, the fins are made of two main components.[8] The first component is the dermal fin rays known as lepidotrichia, and the endoskeletal base with associated muscles for movement is the second.[7]

-

Dorsal fin of a perch showing the basals and radials of the pterygiophore that support the dorsal fin.

-

Closeup of the dorsal fin of a common dragonet

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wright, Jeremy J. (4 December 2009). "Diversity, phylogenetic distribution, and origins of venomous catfishes". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9 (1): 282. Bibcode:2009BMCEE...9..282W. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-282. PMC 2791775. PMID 19961571.

- ^ "Spiny Dogfish". Oceana. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- ^ McGrouther, M. (October 2006). "Port Jackson Shark". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Aquatic Life of the World pp. 332–333, Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2000. ISBN 9780761471707.

- ^ Dement J Species Spotlight: Atlantic Sailfish (Istiophorus albicans) littoralsociety.org. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Lingham‐Soliar T (2005) "Dorsal fin in the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias: A dynamic stabilizer for fast swimming" Journal of Morphology, 263 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/jmor.10207 pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Tohru, Suzuki (2003). "Differentiation of chondrocytes and scleroblasts during dorsal fin skeletogenesis in flounder larvae". Development, Growth & Differentiation. 45 (5–6): 435–448. doi:10.1111/j.1440-169X.2003.00711.x. PMID 14706069. S2CID 13621022.

- ^ a b c Barton, Michael (2007). Bond's Book of Fish (3rd ed.). The Thompson Corporation. pp. 37–39, 60–61.