Rabban Bar Sauma

ܒܪ ܨܘܡܐ Bar Ṣawma ("Son of Fasting") | |

|---|---|

| Church | Church of the East |

| See | Baghdad |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1220 |

| Died | January 1294 (aged c. 73–74) Baghdad, Ilkhanate |

| Denomination | Church of the East |

| Residence | Baghdad, Maragheh |

| Occupation | Monk, ambassador, writer |

Rabban Bar Ṣawma (Syriac language: ܪܒܢ ܒܪ ܨܘܡܐ, [rɑbbɑn bɑrsˤɑwma]; c. 1220 – January 1294), also known as Rabban Ṣawma or Rabban Çauma[2] (simplified Chinese: 拉班·扫马; traditional Chinese: 拉賓掃務瑪; pinyin: lābīn sǎowùmǎ), was a Uyghur or Ongud monk turned diplomat of the "Nestorian" Church of the East in China. He is known for embarking on a pilgrimage from Yuan China to Jerusalem with one of his students, Markos (later Patriarch Yahballaha III). Due to military unrest along the way, they never reached their destination, but instead spent many years in Ilkhanate-controlled Baghdad.

The younger Markos was eventually elected Yahballaha III, Patriarch of the Church of the East and later suggested his teacher Rabban Bar Ṣawma be sent on another mission, as Mongol ambassador to Europe. The elderly monk met with many of the European monarchs, as well as the Pope, in attempts to arrange a Franco-Mongol alliance. The mission bore no fruit, but in his later years in Baghdad, Rabban Bar Ṣawma documented his lifetime of travel. His written account of his journeys is of unique interest to modern historians, as it gives a picture of medieval Europe at the close of the Crusades, painted by a keenly-intelligent, broadminded, and statesmanlike observer.[3]

Bar Ṣawma's travels occurred before the return of Marco Polo to Europe, and his writings give a reverse viewpoint, of the East looking to the West.

Early life

[edit]Right image: Wall painting from a Christian church showing a scene of preaching on Palm Sunday, Qocho (now Gaochang, China), 683–770 AD

Rabban ("monk" in Syriac) Bar Ṣawma was born c. 1220 in or near modern-day Beijing, known then as Zhongdu,[4] later as Khanbaliq under Mongol rule. According to Bar Hebraeus he was of Uyghur origin.[5] Chinese accounts describe his heritage as Öngüd, a Turkic people classified as members of the "Mongol" caste under Yuan law.[6] The name bar Ṣawma is Aramaic for "Son of Fasting"[7] though he was born to a wealthy family. He was a "Church of the East Christian", and became an ascetic monk around the age of 20 and then a religious teacher for decades.

Pilgrimage to Jerusalem

[edit]In his middle age, Rabban Bar Sauma and one of his younger students, Rabban Markos, embarked on a journey from Yuan China to make pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[8] They traveled by way of the former Tangut country, Khotan, Kashgar, Taraz in the Syr Darya valley, Khorasan (now Afghanistan), Maragha (now Azerbaijan) and Mosul, arriving at Ani in the Kingdom of Georgia. Warnings of danger on the routes to southern Syria turned them from their purpose,[3] and they traveled to Mongol-controlled Persia, the Ilkhanate, where they were welcomed by Patriarch Denha I of the Church of the East. The Patriarch requested the two monks to visit the court of the Mongol Ilkhanate ruler Abaqa Khan, to obtain confirmation letters for Mar Denha's ordination as Patriarch in 1266. During the journey, Rabban Markos was declared a "Nestorian" bishop. The Patriarch then attempted to send the monks as messengers back to China, but military conflict along the route delayed their departure, and they remained in Baghdad. When the Patriarch died, Rabban Markos was elected as his replacement, Yahballaha III, in 1281. The two monks traveled to Maragheh to have the selection confirmed by Abaqa, but the Ilkhanate khan died before their arrival, and was succeeded by his son, Arghun.

It was Arghun's desire to form a strategic Franco-Mongol alliance with the Christian Europeans against their common enemy, the Muslim Mamluk Sultanate at Cairo. A few years later, the new patriarch Yahballaha III suggested his former teacher Rabban Bar Ṣawma for the embassy, to meet with the Pope and the European monarchs.

Ambassador to Europe

[edit]In 1287, the elderly Bar Sauma embarked on his journey to Europe, bearing gifts and letters from Arghun to the Eastern Roman emperor, the Pope, and the European kings.[3] He followed the embassy of another "Nestorian", Isa Kelemechi, sent by Arghun to Pope Honorius IV, in 1285.[9][10]

Rabban Bar Sauma traveled with a large retinue of assistants, and 30 riding animals. Companions included the Church of the East Christian (archaon) Sabadinus; Thomas de Anfusis (or Tommaso d'Anfossi),[11] who helped as interpreter and was also a member of a famous Genoese banking company;[12] and an Italian interpreter named Uguetus or Ugeto (Ughetto).[13][14] Bar Sauma likely did not speak any European languages, though he was known to be fluent in Chinese, Turkic, and Persian, and he was able to read Syriac.[15] Europeans communicated to him in Persian.[16]

He traveled overland through Armenia to either the Empire of Trebizond or through the Sultanate of Rum to the Simisso[17] on the Black Sea, then by boat to Constantinople, where he had an audience with Andronicus II Palaeologus. Bar Sauma's writings give a particularly enthusiastic description of the beautiful Hagia Sophia.[3] He next traveled to Italy, again journeying by ship. As their course took them past the island of Sicily, he witnessed and recorded the great eruption of Mount Etna on 18 June 1287. A few days after his arrival, he also witnessed a naval battle in the Bay of Sorrento on St. John's Day, 24 June 1287, during the conflict of the Sicilian Vespers. The battle was between the fleet of Charles II (whom he calls Irid Shardalo, i.e. "Il re Charles Due"), who had welcomed him in his realm, and James II of Aragon, king of Sicily (whom he calls Irid Arkon, i.e. "Il re de Aragon"). According to Bar Sauma, James II was victorious, and his forces killed 12,000 men.

He next traveled to Rome, but too late to meet Pope Honorius IV, who had recently died. So Bar Sauma instead engaged in negotiations with the cardinals,[3] and visited St. Peter's Basilica.

Bar Sauma next made stops in Tuscany (Thuzkan) and the Republic of Genoa, on his way to Paris. He spent the winter of 1287–1288 in Genoa, a famous banking capital.[12] In France (Frangestan), he spent one month with King Philip the Fair, who seemingly responded positively to the arrival of the Mongol embassy, gave him numerous presents, and sent one of his noblemen, Gobert de Helleville, to accompany Bar Sauma back to Mongol lands. Gobert de Helleville departed on 2 February 1288, with clercs Robert de Senlis and Guillaume de Bruyères, as well as l'arbalétrier (crossbowman) Audin de Bourges. They joined Bar Sauma when he later returned through Rome, and accompanied him back to Persia.[18][19]

In Gascony in southern France, which at that time was in English hands, Bar Sauma met King Edward I of England, probably in the capital of Bordeaux. Edward responded enthusiastically to the embassy, but ultimately proved unable to join a military alliance due to conflict at home, especially with the Welsh and the Scots.

Upon returning to Rome, Bar Sauma was cordially received by the newly elected Pope Nicholas IV, who gave him communion on Palm Sunday, 1288, allowing him to celebrate his own Eucharist in the capital of Latin Christianity.[3] Nicholas commissioned Bar Sauma to visit the Christians of the East, and entrusted to him a precious tiara to be presented to Mar Yahballaha[3] (Rabban Bar Sauma's former student, Markos). Bar Sauma then returned to Baghdad in 1288, carrying messages and many other gifts from the various European leaders.[20]

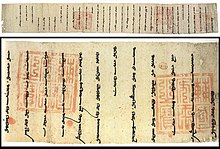

The delivered letters were in turn answered by Arghun in 1289, forwarded by the Genoese merchant Buscarello de Ghizolfi, a diplomatic agent for the Il-khans. In the letter to Philip IV, Arghun mentions Bar Sauma:[21]

"Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Rabban Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year’s winter [1290], worshiping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring [1291].

If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshiping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

— France royal archives[22]

The exchanges towards the formation of an alliance with the Europeans ultimately proved fruitless, and Arghun's attempts were eventually abandoned.[2] However, Rabban Bar Sauma did succeed in making some important contacts which encouraged communication and trade between the East and West. Aside from King Philip's embassy to the Mongols, the Papacy also sent missionaries such as Giovanni da Montecorvino to the Mongol court.

Later years

[edit]After his embassy to Europe, Bar Sauma lived out the rest of his years in Baghdad. It was probably during this time that he wrote the account of his travels, which was published in French in 1895 and in English in 1928 as The Monks of Kublai Khan, Emperor of China or The History of the Life and Travels of Rabban Sawma, Envoy and Plenipotentiary of the Mongol Khans to the Kings of Europe, and Markos Who as Mar Yahbh-Allaha III Became Patriarch of the Church of the East in Asia, translated and edited by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. The narrative is unique for its observations of medieval Europe during the end of the Crusading period, through the eyes of an observant outsider from a culture thousands of miles away.

Rabban Bar Sauma died in 1294, in Baghdad.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Rossabi, Morris (2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. p. 670. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ^ a b Mantran, p. 298

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 767.

- ^ Kathleen Kuiper & editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (31 August 2006). "Rabban bar Sauma: Mongol Envoy." Encyclopædia Britannica (online source). Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Carter, Thomas Francis (1955). The invention of printing in China and its spread westward. Ronald Press Co. p. 171.

- ^ Moule, A. C., Christians in China before 1550 (1930; 2011 reprint), 94 & 103; also Pelliot, Paul in T'oung-pao 15(1914), pp.630–36.

- ^ Phillips, p. 123

- ^ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 376. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410 Peter Jackson p.169

- ^ The Cambridge history of Iran William Bayne Fisher, John Andrew Boyle p.370

- ^ Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 387–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ^ a b Phillips, p. 102

- ^ Grousset, p.845

- ^ Rossabi, pp. 103–104

- ^ Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 385–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ^ Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 386–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ^ Zehiroğlu, Ahmet M. (2014) Bar Sauma's Black Sea Journey

- ^ René Grousset, Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem, vol. III, p. 718

- ^ Pierre Klein, La pérégrination vers l'occident: De Pékin à Paris, le voyage de deux moines nestoriens au temps de Marco Polo (ISBN 978-2-88086-492-7), p. 224

- ^ Boyle, in Camb. Hist. Iran V, pp. 370–71; Budge, pp. 165–97. Source Archived 4 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica Source Archived 4 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Source Archived 2008-06-18 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- Beazley, C. R., Dawn of Modern Geography, ii.15, 352; iii.12, 189–190, 539–541.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1969). "Rabban Ṣauma à Constantinople (1287)". Mémorial Mgr Gabriel Khouri-Sarkis (1898-1968). Louvain: Imprimerie orientaliste. pp. 245–253.

- Chabot, J. B.'s translation and edition of the Histoire du Patriarche Mar Jabalaha III. et du moine Rabban Cauma (from the Syriac) in Revue de l'Orient Latin, 1893, pp. 566–610; 1894, pp. 73–143, 235–300

- Mantran, Robert (1986). "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam". In Fossier, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250–1520. volume 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26646-8.

- Odericus Raynaldus, Annales Ecclesiastici (continuation of Baronius), AD 1288, f xxxv-xxxvi; 1289, lxi

- Phillips, J. R. S. (1998). The Medieval Expansion of Europe (second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820740-9.

- Records of the Wardrobe and Household, 1286-89, ed. Byerly and Byerly (HMSO, 1986), nos. 543, 1082 (for the meeting with Edward I at St Sever).

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-1650-6.

- Wadding, Luke, Annales Minorum, v.169, 196, 170-173

- Zehiroglu, Ahmet M. (2014); "Bar Sauma's Black Sea Journey"

Translations

[edit]Rabban Bar Sauma's travel narrative has been translated into English twice:

- Montgomery, James A., History of Yaballaha III, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1927)

- Budge, E. A. Wallis, The Monks of Kublai Khan, (London: Religious Tract Society, 1928). Online

A critical edition of the Syriac text with an English translation was published in 2021:

- Borbone, Pier Giorgio, History of Mar Yahballaha and Rabban Sauma. Edited, translated, and annotated by -, (Hamburg, Verlag tredition, 2021)

External links

[edit]- The history and Life of Rabban Bar Sauma. (online)