Afonso V of Portugal

| Afonso V | |

|---|---|

Contemporary portrait in the Itinerarium of Georg von Ehingen, c. 1470 | |

| King of Portugal | |

| Reign | 13 September 1438 – 11 November 1477 |

| Acclamation | 15 January 1446 |

| Predecessor | Edward |

| Successor | John II |

| Reign | 15 November 1477 – 28 August 1481 |

| Predecessor | John II |

| Successor | John II |

| Regents | See list

|

| Born | 15 January 1432 Sintra Palace, Portugal |

| Died | 28 August 1481 (aged 49) Lisbon, Portugal |

| Burial | |

| Spouses | |

| Issue | |

| House | Aviz |

| Father | Edward, King of Portugal |

| Mother | Eleanor of Aragon |

| Signature | |

Afonso V[a] (European Portuguese: [ɐˈfõsu]; 15 January 1432 – 28 August 1481), known by the sobriquet the African (Portuguese: o Africano), was King of Portugal from 1438 until his death in 1481, with a brief interruption in 1477. His sobriquet refers to his military conquests in Northern Africa.

Early life

[edit]

Born in Sintra on 15 January 1432, Afonso was the second son of King Edward of Portugal by his wife Eleanor of Aragon.[1] Following the death of his older brother, Infante João (1429–1433), Afonso acceded to the position of heir apparent and was made the first Prince of Portugal by his father, who sought to emulate the English court's custom of a dynastic title that distinguished the heir apparent from the other children of the monarch.[2] He was only six years old when he succeeded his father in 1438.[3][4]

During his minority, Afonso was placed under the regency of his mother, Eleanor, in accordance with the will left by his late father.[5][6] As both a foreigner and a woman, the queen was not a popular choice for regent.[2] When the cortes met in late 1438, a law was passed requiring a joint regency consisting of Eleanor and Pedro, Duke of Coimbra, the younger brother of the late king.[7] The dual regency was a failure and in 1439, the cortes named Pedro "protector and guardian" of the king and "ruler and defender" of the kingdom.[8][9] Eleanor attempted to resist, but without support in Portugal she fled to Castile.[10]

Pedro's regency was characterized by political unrest and weakened authority caused by strife with Afonso, Count of Barcelos, his half-brother and political enemy.[11] In 1441, Afonso's V betrothal to Pedro's eldest daughter, Isabella, was arranged.[12] The engagement caused a conflict between Pedro and the Count of Barcelos, who had wished for the monarch to marry his granddaughter.[13][14]

Afonso reached the age of majority in 1446, but Pedro retained administrative power and the title of regent.[15] Afonso and Isabella were formally married on 6 May 1447,[12] seemingly strengthening Pedro's power at court.[16] However, the Count of Barcelos began to wield more influence over the young king and persuaded him to dispense Pedro in July 1448.[15][16] On 15 September of the same year, Afonso V nullified all the laws and edicts approved under the regency.[16] Tensions escalated and in early 1449 Pedro marched his ducal army towards Lisbon, igniting a brief civil war.[17] Pedro was eventually defeated and killed by Afonso V's royal forces in the Battle of Alfarrobeira in May 1449.[15]

Rule

[edit]Administration

[edit]Afonso financially supported the exploration of the Atlantic Ocean led by his uncle Prince Henry the Navigator.[18] In February 1449, he granted Henry monopoly over navigation in the African Atlantic between Capes Cantin and Bojador.[19] The grant caused conflict with John II of Castile, who asserted that conquest of Barbary and Guinea were reserved for the Castilian crown.[20] John II was also angered by Henry's conduct in the Canary Islands and repeatedly wrote to Afonso complaining about displays of hostility, such as attacks on Castilian shipping.[21] Tensions finally deescalated with the marriage of Afonso's youngest sister, Joan, to John II's heir, Henry, in 1455.[22]

In 1452, Pope Nicholas V issued the papal bull Dum Diversas, which granted Afonso V the right to reduce "Saracens, pagans and any other unbelievers" to hereditary slavery. This was reaffirmed and extended in the Romanus Pontifex bull of 1455 (also by Nicholas V). These papal bulls came to be seen by some as a justification for the subsequent era of slave trade and European colonialism.[23]

After Henry's death in 1460, his nephew Ferdinand inherited his titles and rights but the monopoly over trade reverted to the crown.[24] In 1469, Afonso V granted Fernão Gomes the monopoly of trade in the Gulf of Guinea.[25]

Invasion of Morocco

[edit]

Afonso V's interest in Africa was sparked by a desire to support Papal efforts against Islam, especially after the fall of Constantinople in 1453.[26] A large crusade was desired but the Papacy struggled to rally the necessary forces and Afonso, having already made war preparations in Portugal, saw an opportunity to pursue military campaigns in Africa.[18]

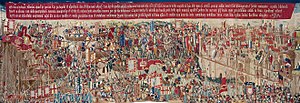

In 1458, Afonso V, leading an expeditionary force of 25,000 men, assaulted and captured the town of Alcácer Ceguer.[27][28] After the conquest, he gave himself the title "king of Portugal and the Algarves", where the plural form of Algarve was meant to refer to both the original Kingdom of the Algarve in southern Portuguese as well as the new territories in Africa.[29][30] For the next two decades, the Portuguese nobility and crown concentrated their efforts primarily on Morocco.[31] Between November 1463 and April 1464, Afonso made multiple unsuccessful attempts to sieze Tangiers.[32] In August 1471, he launched another campaign with the intention of capturing the city, but his fleet was diverted by a storm to the port of Arzila.[33] After a fierce battle, Arzila was captured.[34] Subsequently, the nearby population of Tangiers fled and the city fell into Portuguese control.[35] His victories earned the king the nickname of the African or O Africano.[36]

War with Castile

[edit]

Following his campaigns in Africa, Afonso V found new grounds for battle in neighboring Castile.[37] On 11 December 1474 King Henry IV of Castile died without a male heir, leaving just one daughter, Joanna. However, her paternity was questioned; it was rumored that his wife, Queen Joan of Portugal (Afonso's sister) had an affair with a nobleman named Beltrán de La Cueva.[38] The death of Henry ignited a war of succession, with one faction supporting Joanna and the other supporting Isabella, Henry's half-sister. Afonso V was persuaded to intervene on behalf of Joanna, his niece.[39][40]

On 12 May 1475 Afonso entered Castile with an army of 5,600 cavalry and 14,000 foot soldiers.[41] He met Joanna in Palencia and the two were betrothed and proclaimed sovereigns of Castile on 25 May.[42] The formal marriage was delayed because their close blood-relationship necessitated a papal dispensation.[43]

In March 1476, after several skirmishes and much maneuvering, the 8,000 men of Afonso and Prince John, faced a Castilian force of similar size in the Battle of Toro. The Castilians were led by Isabella's husband, Prince Ferdinand II of Aragon, Cardinal Mendoza and the Duke of Alba.[44] The fight was fierce and confusing but the result was a stalemate:[45][46][47] while the forces of Cardinal Mendoza and the Duke of Alba won over their opponents led by the Portuguese king—who left the battlefield to take refuge in Castronuño—the troops commanded by Prince John defeated and persecuted the troops of the Castilian right wing and recovered the Portuguese royal standard, remaining ordered in the battlefield where they collected the fugitives of Afonso.[48] Both sides claimed victory, but Afonso's prospects for obtaining the Castilian crown were severely damaged.[49]

After the battle, Afonso sailed to France hoping to obtain the assistance of King Louis XI in his fight against Castile.[50] In September 1477, disheartened that his efforts to secure support had proved fruitless, Afonso abdicated the throne and embarked on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[51][52] He was eventually persuaded to return to Portugal, where he arrived in November 1477.[53] Prince John had been proclaimed king days prior to Afonso's arrival, but relinquished his new title and insisted that his father reassume the crown.[54][55]

From 1477 to 1481, Afonso V and Prince John were "practically corulers."[55] Afonso made preparations for a second invasion of Castile in winter 1478, but was deterred by Castilian Hermandad forces.[56] The Treaty of Alcáçovas was finally negotiated in 1479, wherein Afonso renounced his claim to the Castilian throne in exchange for Portuguese hegemony in the Atlantic south of the Canary Islands.[57][58][59] Although the treaty was advantageous for Portugal, the king was deeply unhappy with the provision that forced his bride and niece, Joanna, into a convent.[60][61] Withdrawn and melancholic, he announced his intention to abdicate[b] for a second time and retired to a monastery in Sintra.[62][63] He died of fever shortly after, on 28 August 1481.[64]

Marriages and descendants

[edit]Afonso married, firstly, in 1447, his first cousin Isabella of Coimbra, with whom he had three children:[65]

- John, Prince of Portugal (29 January 1451)

- Joan, Princess of Portugal (6 February 1452 – 12 May 1490) – known as Saint Joan of Portugal, or Saint Joan Princes

- John II of Portugal (3 March 1455 – 25 October 1495) – succeeded his father as 13th King of Portugal

After the death of his wife in 1455, he had at least one child out of wedlock with Maria Soares da Cunha, daughter of Afonso's major valet, Fernao de Sa Alcoforado:[citation needed]

- Álvaro Soares da Cunha (1466–1557), Noble of the Royal House, Lord of the House of Quintas in Sao Vicente de Pinheiro, Porto and Chief Guard of Pestilence in Porto

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Afonso V of Portugal |

|---|

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Pereira & Rodrigues 1904, p. 64.

- ^ a b Livermore 1947, p. 196.

- ^ Flood 2019, p. 189.

- ^ Marques 1976, p. 131.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 413.

- ^ Disney 2009, p. 128.

- ^ Stephens 1891, p. 130.

- ^ Disney 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Stephens 1891, p. 131.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 433.

- ^ Marques 1976, p. 132.

- ^ a b Rogers 1961, p. 59.

- ^ Rogers 1961, pp. 60, 86.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 415.

- ^ a b c Livermore 1947, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Disney 2009, p. 139.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, pp. 479–481.

- ^ a b Livermore 1947, p. 204.

- ^ Russell 2000, pp. 218–221.

- ^ Russell 2000, p. 222.

- ^ Russell 2000, pp. 270–284.

- ^ Russell 2000, p. 285.

- ^ Gill, Joseph. "Nicholas V". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Scafidi, Oscar (2015). Equatorial Guinea. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84162-925-4.

- ^ Marques 1976, p. 207.

- ^ Pereira & Rodrigues 1904, p. 65.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, pp. 501–502.

- ^ Marques 1976, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Sousa 1998, p. 641.

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Livermore 1947, p. 205.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 505.

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Pereira & Rodrigues 1904, p. 66.

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Stephens 1891, p. 134.

- ^ Stuart 1991, p. 37.

- ^ Marques 1976, p. 208.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 509.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 510.

- ^ Stuart 1991, p. 136.

- ^ Stuart 1991, p. 137.

- ^ Esparza, José J. (2013). ¡Santiago y cierra, España! (in Spanish). La Esfera de los Libros.

It was 1 March 1476. Eight thousand men for each side, the chronicles tell. With Afonso of Portugal were his son João and the bishops of Evora and Toledo. With Fernando of Aragón, Cardinal Mendoza and the Duke of Alba, as well as the militias of Zamora, Ciudad Rodrigo and Valladolid. The battle was long, but not especially bloody: it is estimated that the casualties of each side did not reach a thousand.

- ^ Bury, John B (1959). The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 8. Macmillan. p. 523.

After nine months, occupied with frontier raids and fruitless negotiations, the Castilian and Portuguese armies met at Toro ... and fought an indecisive battle, for while Afonso was beaten and fled, his son John destroyed the forces opposed to him.

- ^ Dumont, Jean (1993). La "imcomparable" Isabel la Catolica [The incomparable Isabel the Catholic] (Spanish ed.). Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. p. 49.

...But in the left [Portuguese] Wing, in front of the Asturians and Galician, the reinforcement army of the Prince heir of Portugal, well provided with artillery, could leave the battlefield with its head high. The battle resulted this way, inconclusive. But its global result stays after that decided by the withdrawal of the Portuguese King, the surrender... of the Zamora's fortress on 19 March, and the multiple adhesions of the nobles to the young princes.

- ^ Desormeaux, Joseph-Louis (1758). Abrégé chronologique de l'histoire d'Espagne. Vol. III. Paris: Duchesne. p. 25.

... The result of the battle was very uncertain; Ferdinand defeated the enemy's right wing led by Afonso, but the Prince had the same advantage over the Castilians.

- ^ Downey, Kirstin (2014). Isabella: the Warrior Queen. New York: Anchor Books. p. 145.

The two sides finally and climactically clashed, in the major confrontation known as the Battle of Toro, on 1 March 1476. The Portuguese army, led by King Afonso, his twenty-one-year-old son Prince João, and the rebellious Archbishop Carrillo of Toledo opposed Ferdinand, the Duke of Alba, Cardinal Mendoza, and other Castilian nobles leading the Isabelline forces. Foggy and rainy, it was bloody chaos on the battlefield. (...) Hundreds of people – perhaps as many as one thousand – died that day. (...). Troops led by Prince João won in their part of the battle; some troops led by King Ferdinand won in another part. But the most telling fact was that King Afonso had fled the battlefield with his troops in disarray; the Castilians seized his battle flag, the royal standard of Portugal, despite the valiant efforts of a Portuguese soldier, Duarte de Almeida, to retain it. (...). The Portuguese, however, later managed to recover the banner. The battle ended in an inconclusive outcome, but Isabella employed a masterstroke of political theater by recasting events as a stupendous victory for Castile. Each side had won some skirmishes and lost others, but Ferdinand was presented in Castile as the winner and Afonso as a craven failure. (...)..

- ^ Stuart 1991, p. 147.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 516.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Busk 1833, p. 76.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 522.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 523.

- ^ a b Marques 1976, p. 209.

- ^ Stuart 1991, p. 166.

- ^ Stuart 1991, p. 174.

- ^ Marques 1976, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Newitt 2023, p. 126.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 527.

- ^ Stephens 1891, p. 135.

- ^ a b Livermore 1947, p. 210.

- ^ Stuart 1991, p. 176.

- ^ McMurdo 1889, p. 528.

- ^ Freitas 2011, p. 95.

- ^ a b Stephens 1891, p. 139

- ^ a b c d e f de Sousa, Antonio Caetano (1735). Historia genealogica da casa real portugueza [Genealogical History of the Royal House of Portugal] (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Lisboa Occidental. p. 497.

- ^ a b John I, King of Portugal at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b Armitage-Smith, Sydney (1905). John of Gaunt: King of Castile and Leon, Duke of Aquitaine and Lancaster, Earl of Derby, Lincoln, and Leicester, Seneschal of England. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 21. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Busk, M.M (1833). The history of Spain and Portugal from B.C. 1000 to A.D. 1814. London: Baldwin and Cradock.

- Disney, A. R. (2009). A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire. From Beginnings to 1807. Vol. I: Portugal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60397-3.

- Flood, Timothy M. (2019). Rulers and Realms in Medieval Iberia, 711-1492.

- Freitas, Isabel Vaz (2011). D. Isabel de Coimbra: Insigne Rainha (in Portuguese). Quidnovi.

- Livermore, H.V. (1947). A History of Portugal. Cambridge University Press.

- Livermore, H. V. (2003). "Aphonso V". In Gerli, E. Michael (ed.). Medieval Iberia : an encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93918-6. OCLC 50404104.

- López Poza, Sagrario (2019). "La divisa de Alfonso V el Africano, rey de Portugal: nueva lectura e interpretación". Janus. Estudios Sobre el Siglo de Oro (8): 47–74. ISSN 2254-7290.

- Marques, Antonio Henrique R. de Oliveira (1976). History of Portugal (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08353-X.

- McMurdo, Edward (1889). The history of Portugal, from the Commencement of the Monarchy to the Reign of Alfonso III. Vol. II. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington.

- Newitt, Malyn (2023). Navigations: The Portuguese Discoveries and the Renaissance.

- Newitt, Malyn (2005). A history of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1668.

- Pereira, Esteves; Rodrigues, Guilherme (1904). Portugal: diccionario historico, chorographico, heraldico, biographico, bibliographico, numismatico e artistico (in Portuguese). Vol. I. Lisboa: J. Romano Torres.

- Rogers, Francis M. (1961). The Travels of the Infante Dom Pedro of Portugal. Harvard Studies in Romance Languages. Vol. XXVI. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Russell, Peter (2000). Prince Henry 'the Navigator': a Life.

- Saul, António (2009). Dom Afonso V. Reis de Portugal. Vol. 12. Temas e Debates-Actividades Editoriais. ISBN 978-97-2759-975-2.

- Sousa, Armindo de (1998). "Portugal". In Allmand, Christopher (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 7. Cambridge University Press. pp. 627–644. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521382960.032. ISBN 978-0521382960.

- Stephens, H. Morse (1891). The Story of Portugal. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Stuart, Nancy Rubin (1991). Isabella of Castile: The First Renaissance Queen. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-05878-0.